Moving Women’s Fatshion Forward Through The Years - Part 1

By Darliene Howell and Marcy Cruz

Fatshion (the term currently being used for fat fashion) and fatshionistas (those that love fat fashion) are something we see on social media every day. But what do we know of the history of women’s fat fashion?

The history of ready-to-wear clothing began when military uniforms were produced during the War of 1812. Soon after, men’s clothing for men became readily available.(1) There were no ready-to-wear retailers producing fashion for women anywhere. For the most part, women had to either make their clothing themselves or have them made by dressmakers until the beginning of the 20th century.(2)

In 1904, a young widowed dressmaker, Lena Bryant, wanted to open a shop on Fifth Avenue to make money to support her son. Her name was changed to Lane Bryant by a misspelling by a bank official. Asked by one of her pregnant customers to design something "presentable but comfortable" to wear in public, Bryant created a dress with an elasticized waistband and accordion-pleated skirt. This would become the first known commercially made maternity dress. This dress was welcomed not only by middle-class women, but also by poorer pregnant women who had to work. The maternity dress soon became the best-selling garment in Bryant's shop. In 1909, Lena married Albert Malsin, an engineer, who became her business partner and helped expand the sales of maternity clothing through mail order. Having succeeded in maternity wear and catalog sales, Lane Bryant Malsin’s next great innovation was ready-made clothing for the “stout-figured” woman. After measuring some 4,500 women in her store and analyzing statistics gathered on some 200,000 others, Lane Bryant Malsin determined that there were three general types of stout women and she designed clothes to fit each type. In 1915, Lane Bryant opened its first branch retail store, in Chicago. By 1923, company sales had reached five million dollars and sales of full-figured clothing outstripped sales of maternity wear. By 1969 the chain had grown to more than 100 stores with combined sales of $200 million.(3)

Out of that success rose other plus size fashion retailers. Evans, a UK-based plus size retailer offering up to a size 32, was founded in 1930. But as NAAFA founder Bill Fabrey can attest, fashion options for many fat women were few and far between. Bill tells a story about trying to find a blouse for his wife, Joyce’s, birthday. After looking locally, he only found one in the entire town.ONE. But this was only part of why Bill saw the need for change in how fat people are treated. The National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance (then the National Association to Aid Fat Americans) was founded in 1969.

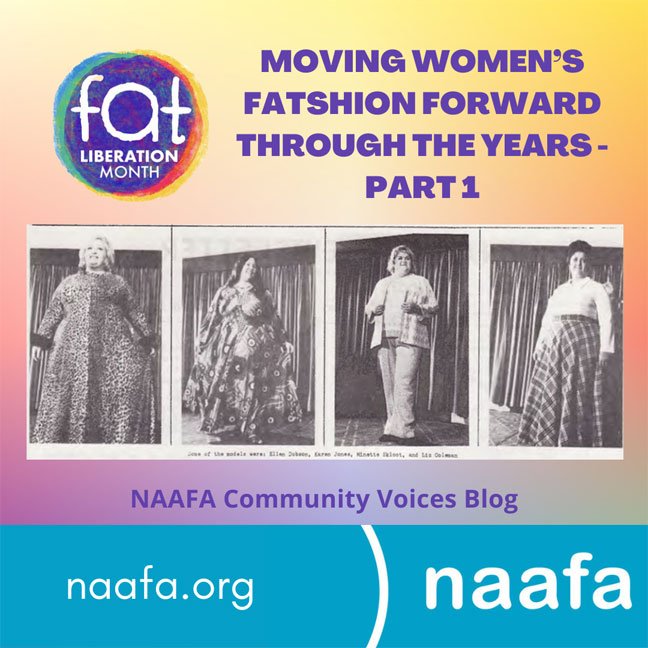

Eileen Lefebure was one of the founding members of NAAFA. She was on the Board of NAAFA and the Recording Secretary. In 1972, NAAFA held a call for models for the 3rd Annual NAAFA Convention in November 1972 and asked interested members to contact Eileen. The 1972 NAAFA Fashion Show is the first documented fashion show of its kind.

Eileen wrote an article about her motivation and the experience in the October 2010 NAAFA Newsletter. In it she states, “A couple of years after the first gathering, I brought up the idea of a Fashion Show as part of the “Convention Day”. The idea was not well received by the board then composed mostly of men. They thought the idea was frivolous and would not bring in any more money. I refused to give up. I was the Board Secretary and I made sure the proposal was on the Board’s agenda each month but it was repeatedly rejected until finally it passed…”

Eileen also noted, “The Convention that year (the first one day event), was in a small hotel on the upper west side of NYC and everyone was aflutter about the Fashion Show. As a result of press releases, there were a number of media representatives there. This event was picked up by “Parade Magazine” who put six models on the cover, including me. Their story featured NAAFA and our large size models resulting in more publicity. NAAFA was prominently featured on local New York television news shows, on radio and in newspapers. There were requests for information from all over the US as well as other countries. This daring show caught the attention of the worldwide media because of the plus size models.”

These shows were pivotal in pushing the message that people wanted to see plus size bodies modeling plus size clothing. For years, plus size clothing manufacturers claimed that people didn’t want to see actual plus size models in the clothes that they offer. NAAFA has always disagreed and our fashion shows and other programming have always proven that sentiment wrong. How do we know how the clothes will look on us if we don’t have examples to show us? Although fashion lines continue to expand their use of plus size models today in 2022, there is still much work to be done in using larger models and offering diversity in bodies shown. We need to see more models that look like us.

In Part 2, we will be looking at how fatshion has been PUSHED forward through the use of larger models, bringing plus sizes to the mainstream, the growth of plus size fatshion influencers in social media and fatshion as activism.

The Modernization of Fashion, Anne Hollander, https://doi.org/10.2307/4091263

American Fashions for American Women: Early Twentieth Century Efforts to Develop an American Fashion Identity, Sara B. Marcketti and Jean L. Parsons, https://dr.lib.iastate.edu/handle/20.500.12876/2226

Jewish Virtual Library, Lena Bryant Malsin, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/lena-bryant-malsin

Darliene Howell has worked directly with NAAFA since her retirement in 2004; first as the recording secretary to the Board of Directors in 2007, was the Chair of the Board in 2015. In 2020, she elected to step down as Chair of the Board and remains Administrative Director. She has been active in fat community 20+ years.

Marcy Cruz is an award-winning writer/author, educator and activist with 20 years of experience in the plus size fashion industry. She is also signed to State Management as an extended-sizes (4X+) fit model and is the content creator of the blog Fearlessly Just Me.

OPINION DISCLAIMER: Any views or opinions stated in the NAAFA Community Voices Blog are personal and belong solely to the blog author. They do not represent the views or opinions of NAAFA or the people, institutions or organizations that the owner may or may not be associated with in professional or personal capacity, unless explicitly stated. Any views or opinions are not intended to malign any religion, ethnic group, club, organization, company, or individual.